От халепа... Ця сторінка ще не має українського перекладу, але ми вже над цим працюємо!

Security in Android: How to build a safe application

Supernerd

/

Developer

9 min read

Fully secure systems don’t exist. – Adi Shamir, co-inventor of the RSA algorithm

Naysayers say there’s no security in Android.

How can we build a safe application then?

Well, we can at least try.

Just imagine: about 70% of mobile users choose Android devices over iOS, even though iOS devices are considered more protected from hackers.

On Android, users can take care of their own mobile security to some extent, with 2FA, VPN, biometric authentication, and wise permission management. But we, as Android developers, want to deliver as much protection as possible.

In this article, we talk about what security means, where to look for security vulnerabilities, and how to implement some best practices to protect against them.

Article content:

Android security: Current status and problems

However, first things first — how do we define security?

Security is a system state where external and internal factors have no negative impact on the system operation.

In plain words, it’s a safe condition where your system or application isn’t at risk and can run seamlessly.

But the thing is, no Android app can be totally secure for four main reasons:

- The Google Play Market is very open environment.

- Users neglect or bypass security features.

- Many apps are downloaded from third parties.

- Almost 70% of Android applications average thirty-nine vulnerabilities in each.

These factors put users’ data at risk, including banking, electronic health information, email and messages, insurance, and other aspects of daily life.

See also: BottomNavigation View with some magic

Top mobile security issues

To help you make your applications safe, we’ve listed the most critical vulnerabilities to keep an eye on.

Weak authentication is one of the trickiest issues. Although users partially control the user authentication process, it’s the developer’s responsibility to make authentication easy and smooth to minimize the number of users who will try to bypass secure sign-ins. Key exchange and authenticating legitimate requests from apps to the back-end are also processes you need to protect against leakage to prevent attacks.

An unprotected data transfer layer leaves open the potential to steal data. Attackers can intercept data during communication between the app and the back end . In this case, a third party can successfully perform hijack request and gain access to the server-side information.

Unsecured native code puts data obtained through a network or via interprocess communications (IPCs) at risk. This can cause buffer overflows and logic errors (e.g., off-by-one errors). Using the Android NDK instead of Android SDK, in general, compromises safety. If you prefer the Android NDK, at least obfuscate the code.

External storage without cryptographic verification leaves the storage device vulnerable to data theft by intruders who can attempt to read and write over the stored data. As a result, it exposes the stored data to attackers.

Fragile cryptography cases, like insecure protocols and poor security token management, also expose sensitive data to questionable third parties.

And that’s just a partial list. We didn’t bring up other careless practices in security in Android, like session mishandling, poor management of access permission requests, and skipping app data containerization. Most probably, that’s because those are the rule of thumb, and that doesn’t mean you can ignore them.

Building a protected Android app: Best practices

Now, let’s go to what you’re all here for — techniques to make your Android apps more secure. Let’s examine them one by one, without a hurry.

Keeping web-traffic safe

There are different ways of attacking apps. We’ll skip the most obvious attacks, like retrieving images, fonts, texts, and animations, and jump right into a more damaging attack: web traffic interception.

An online shopping app is a good example. Nefarious parties can potentially attack them, retrieve their network transmissions and obtain information that lets them create a price comparator app.

Or, web traffic can transfer private keys (e.g., for a paid service that attackers would like to use free) and try to retrieve them from an app. Attackers may try to retrieve them during transfer. Whether the keys are encrypted or unencrypted, intruders can potentially benefit from them.

So the web traffic is our first stop, and let’s look at how to secure it.

Stage 1

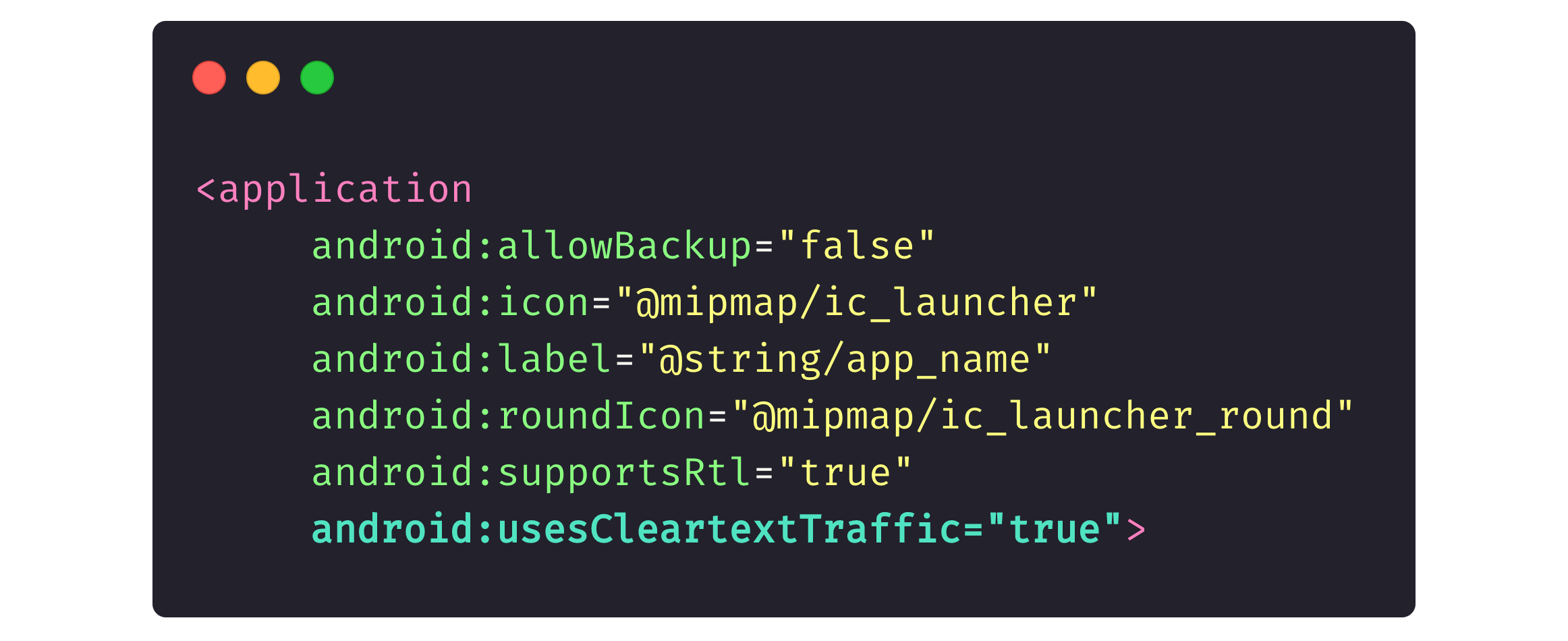

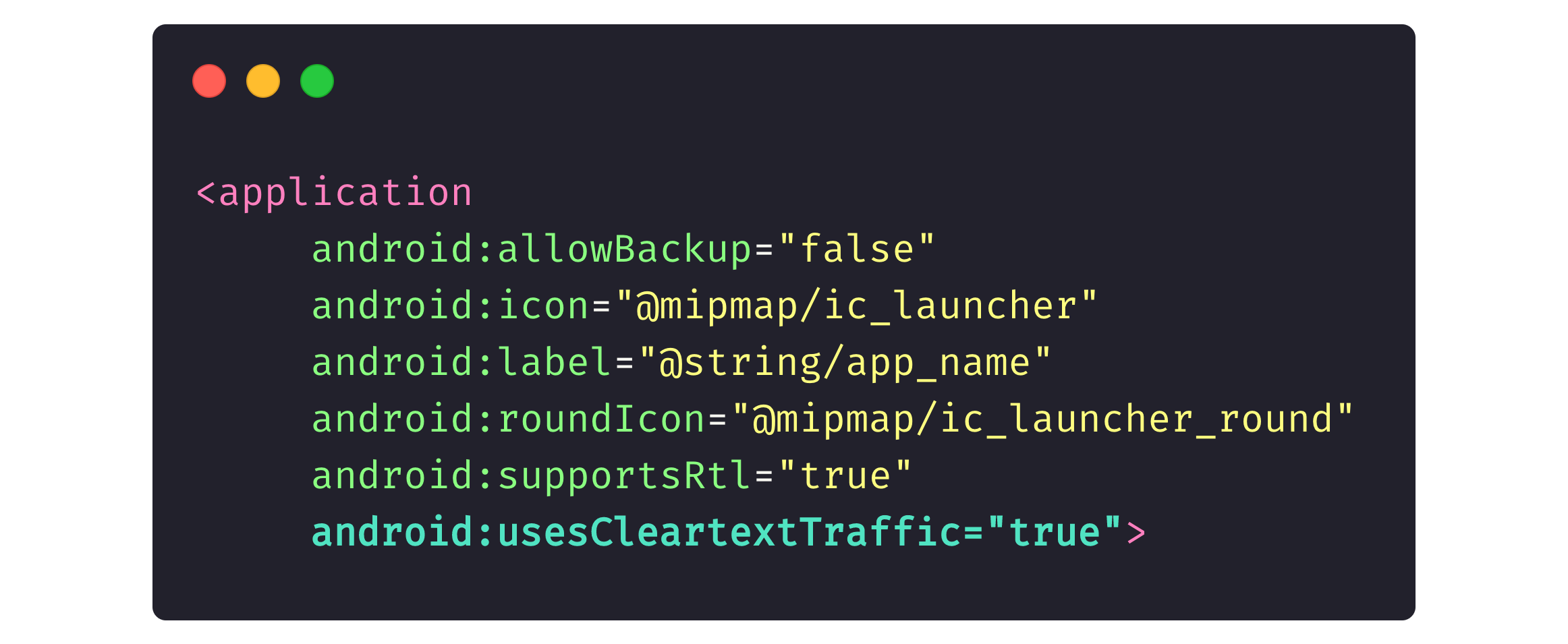

Every Android app includes an AndroidManifest.xml file where we, developers, define permissions that an app can ask a user for, screens an app contains, and other app components.

The picture below reflects part of a generic app description, where android:usesCleartextTraffic=“true” means that we entrust the in-app traffic (both HTTPS and HTTP) entirely to the network.

Stage 2

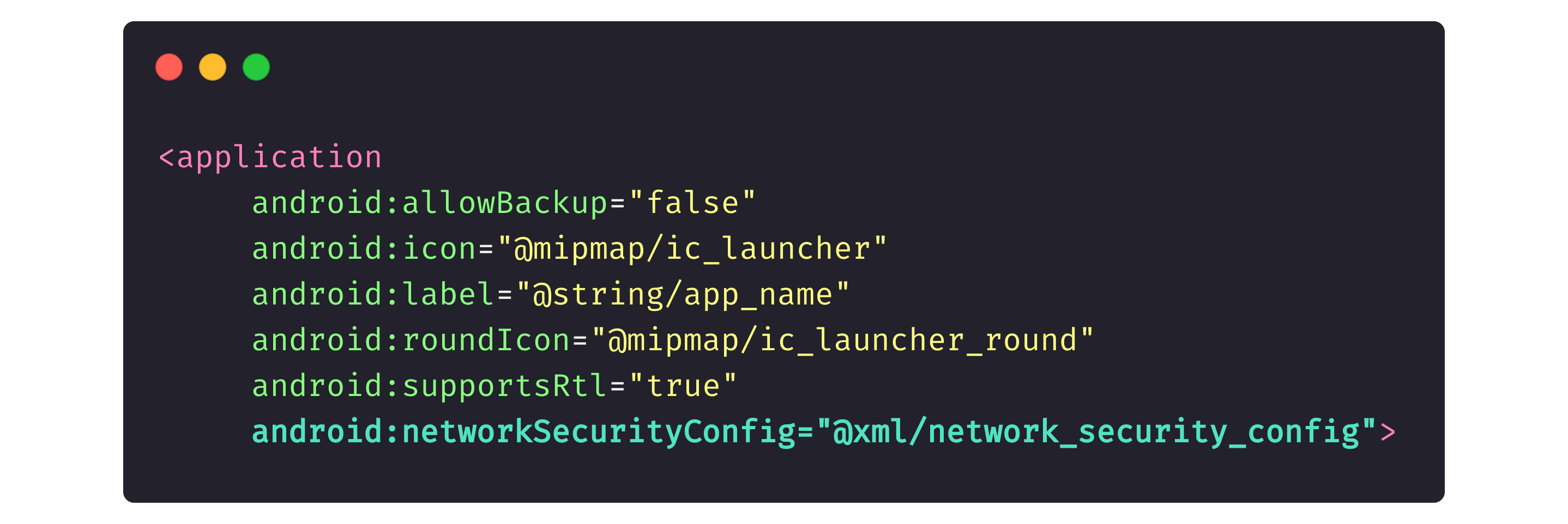

Programs like Proxyman and Charles allow attackers to intercept app traffic and read anything the app sends to the back-end. These programs usually install a certificate on an Android device, allowing an attacker to intercept an app’s web traffic.

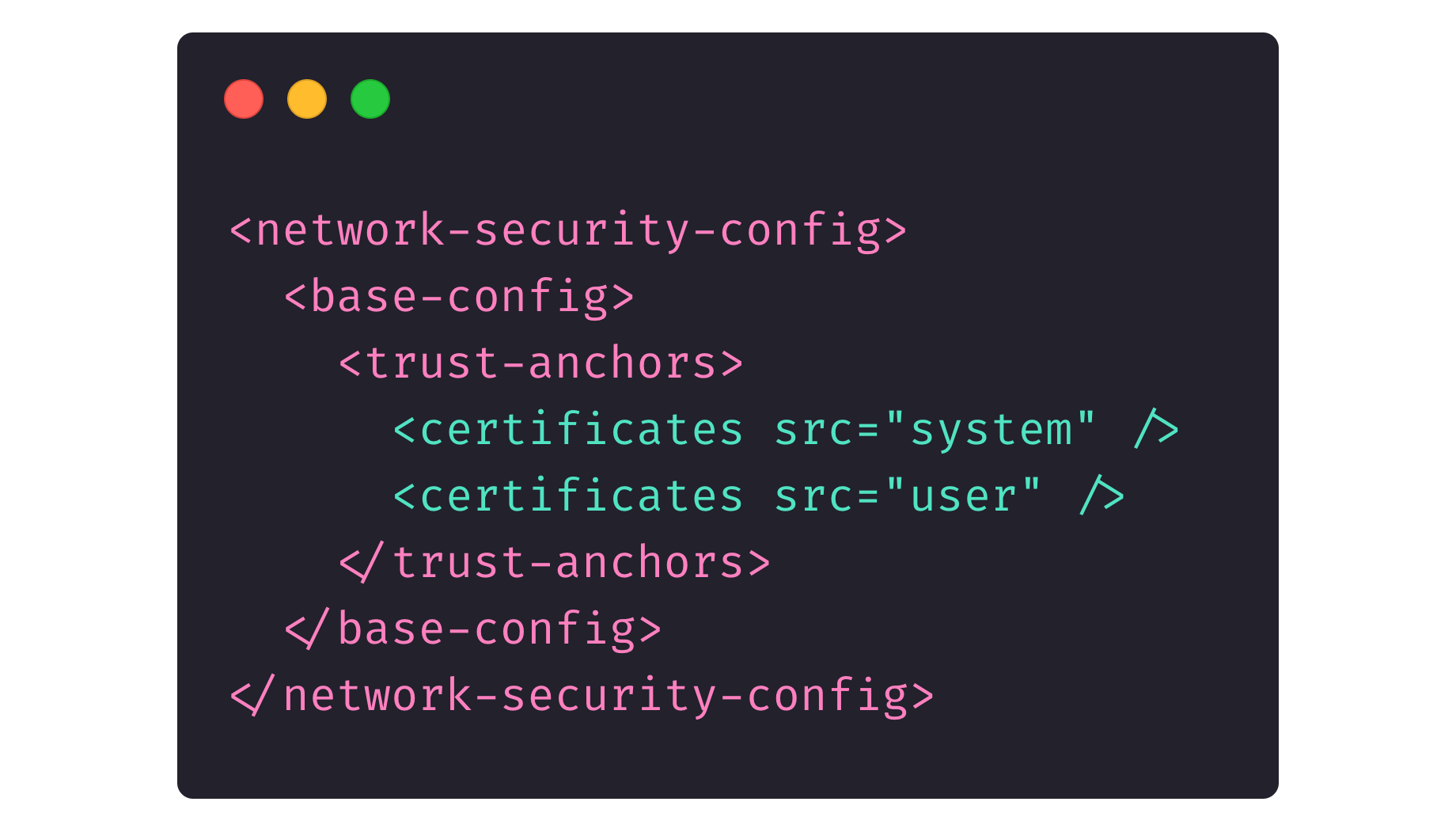

The picture below shows the networkSecurityConfig description in the <application> field of an AndroidManifest.xml file.

Here, we indicate to the device system that our app contains a file that lists certificates our app trusts. Because we didn’t indicate Proxyman or Charles as trusted certificates, if a device has credentials from Proxyman or Charles, those programs won’t be able to read app traffic.

Stage 3

At this stage, we indicate that the beck end only trust specific certificates and nothing more. This protects us from man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks (i.e., for example, when an intruder intercepts traffic at the router level, modifies it, and transmits it to the app).

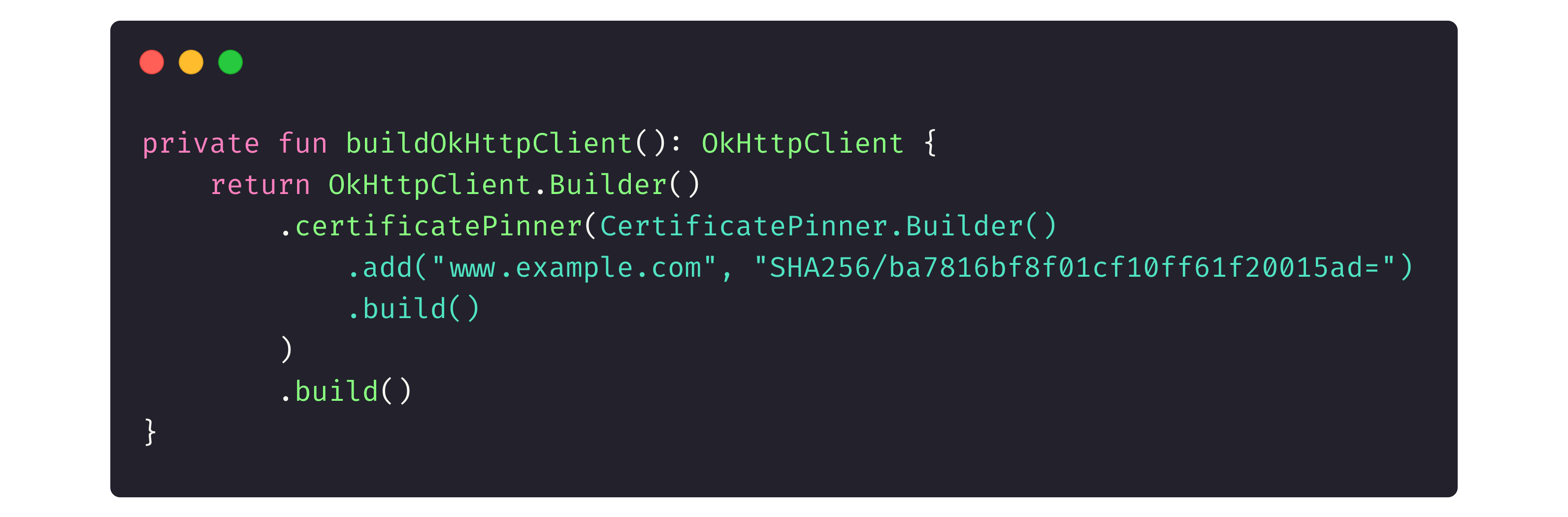

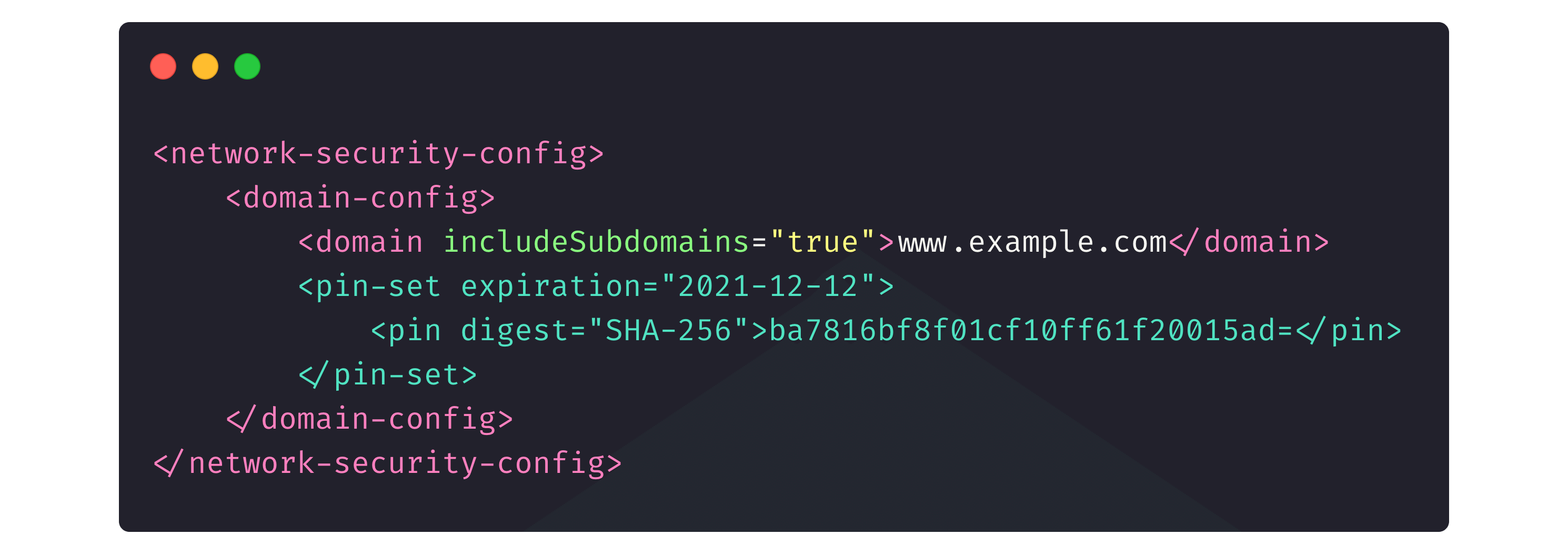

Let’s examine two approaches to configure SSL pinning.

The first method is the code in OkHttpClient, which is, in fact, our intermediary to the in-app web traffic.

The second one is the same networkSecurityConfig that we used in Stage 2 to indicate the trusted certificates.

Keeping your data secure

Unless you live under a rock, you know how important it is to hide an app’s data from evil eyes.

Back-up system

Every app has a cache, local files, and other ways of storing data. Uninstalling an app either deletes those caches and files with the app or they stay on the device (for instance, if a user plans to install the app again and wants to keep the cached files, like pictures, audio, video, or a contact list from the previous installation). Users indicate in the relevant field whether they want to keep the cache or delete it after the app is removed.

Here’s what this looks like in AndroidManifest:

Developers also include a field for users to indicate which particular files they want (or don’t want) to keep after the app is uninstalled. This configuration is obligatory for Android 12 and later versions.

It’s also worth mentioning Android Debug Bridge, or adb. This Android system feature allows users to upload the app’s cache to their PC. This way, when a user chooses not to save the app cache to their PC, they’re protected from attackers who attempt to retrieve it through adb.

If an app has root permission on a device, the attackers can retrieve files from other apps via adb. Finance-related apps generally don’t work on a device if it has root rights. Particular plugins can hide whether an application has root rights, and there are some methods to unveil that information. But that’s a story for another time.

See also: HR Managers in times of war: How the Scandinavian management model helps NERDZ LAB communicate

API keys

You probably already know that API keys must also be stored and used correctly. Let’s compare a few approaches to maintaining them.

- Strings.xlm has a security level of zero, and it’s easy to get the API keys from here. This approach requires .apk or bundle files.

- Constants have the same level of security as the previous one. For some security, it requires code obfuscation and annotation.

- Native libraries, though safer than the previous alternatives, native libraries can be hacked too. You should encrypt native libraries for better security.

- Backend and Keystore have a higher level of security. Just like native libraries, you need to use cryptography with them. This is the preferred way to save API keys.

Database security and its algorithm

First, decide whether database security is critical for you, and if your answer is yes, you should opt for the paid SQLCipher library. It has broader functionality than the free one and it’s obfuscated so that the code is obscure, incomprehensible, and intertwined.

The library works with both standard tools, like SQLite, and modern tools, like Room.

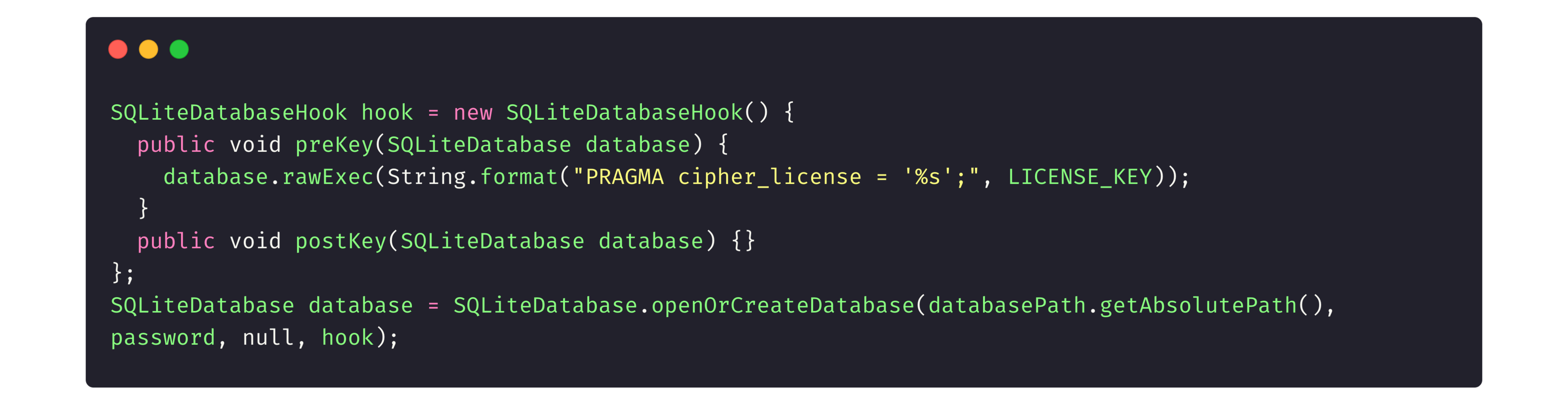

Let’s look at how the SQLCipher library works with an application.

First, we initialize the library.

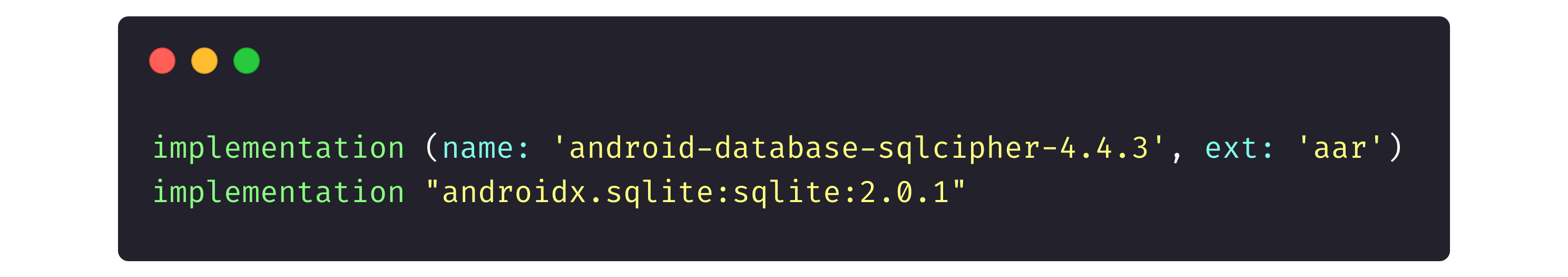

Then, in the Gradle file (another project configuration file to attach different libraries or configure things, like the minimum Android version for app install) we tell the app to call the library.

JetPack

This very comprehensive application component contains two elements to secure user data.

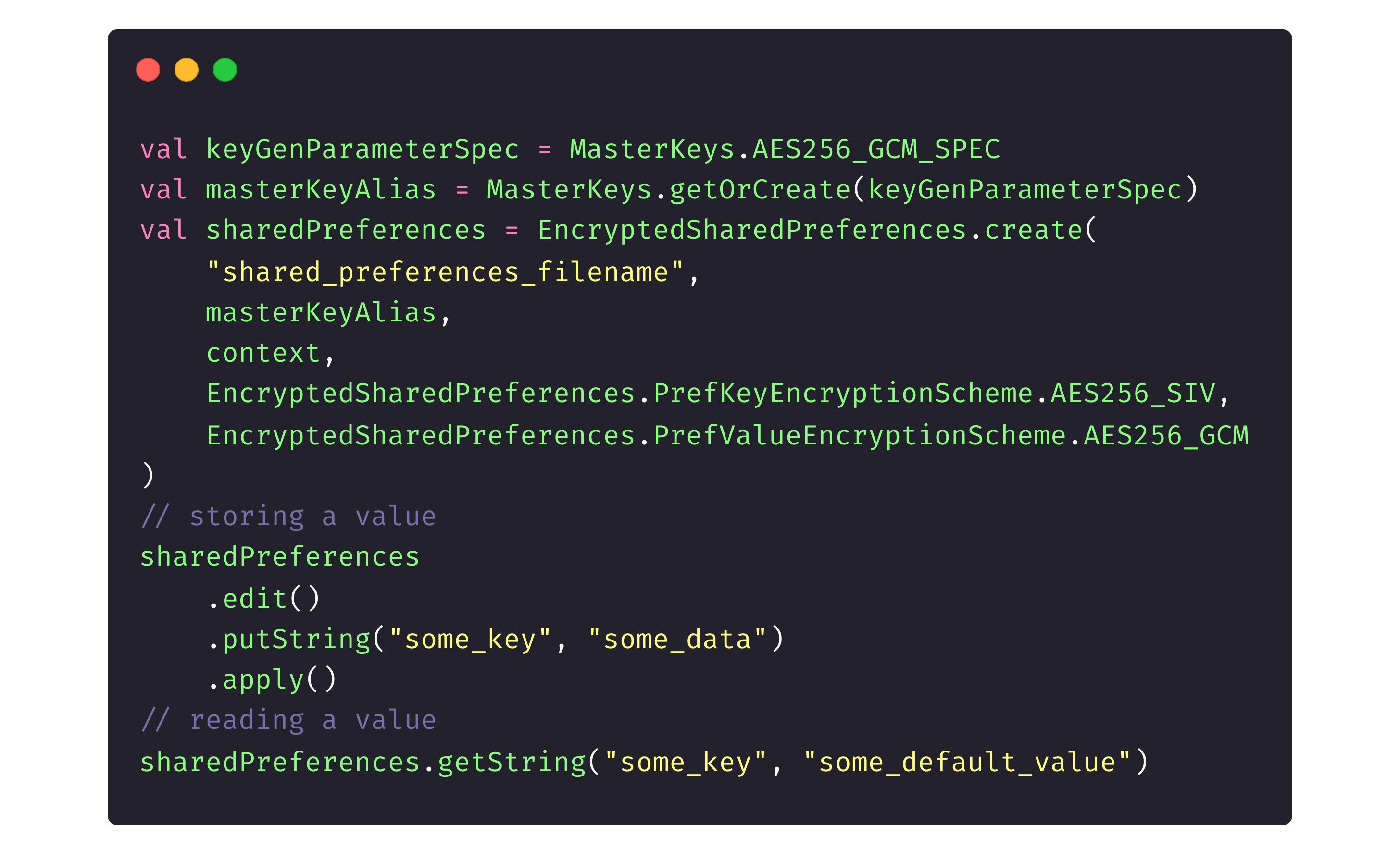

EncryptedSharedPreferences is a file that saves data about particular app elements. It usually holds a user token and their private data, like account information, to quickly show it on-screen.

If we keep the data unencrypted, any attacker who gains access to root permissions on a user’s device can retrieve this file and read all of the user’s data. But when it’s encrypted, attackers only see a set of random letters.

First, we connect the library to the project in the Gradle file:

Then the library initializes and runs its code:

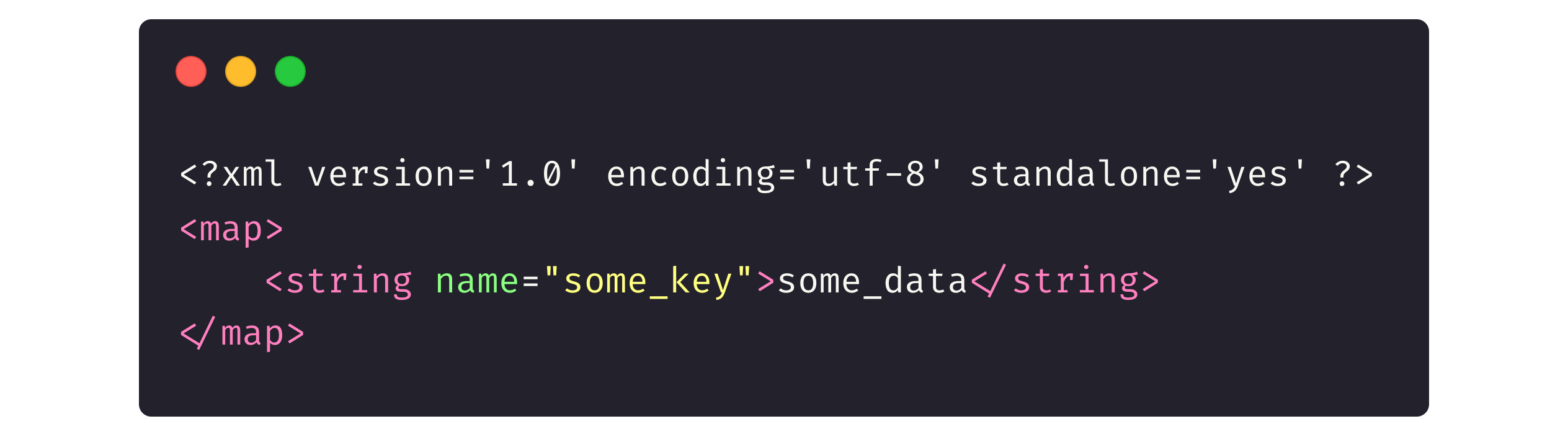

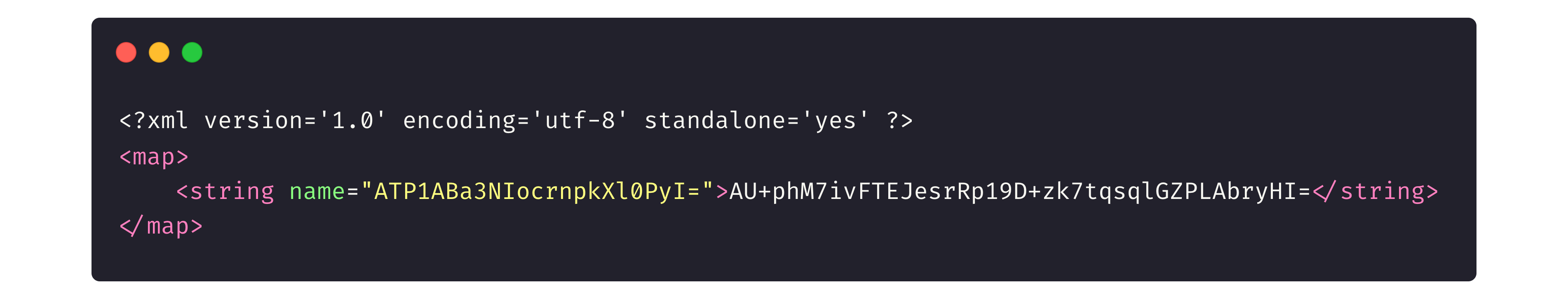

Here’s what the data files retrieved from the app look like unencrypted:

And encrypted with the library:

The EncryptedFile API, meanwhile, can be used to encrypt any file, being supported by Android 6 and later versions. This encryption tool uses the Tink library under the hood and provides custom implementations of FileInputStream and FileOutputStream.

Netflix and YouTube often use EncryptedFile to encrypt the audio and video files that users download for offline listening and watching (for premium accounts, of course). As you can see in the relevant folder, the system indicates these downloaded files as encrypted.

Keystore

The Android Keystore system can serve as a container for private keys from different services. The keystore represents an extra protection level beyond the previous ones.

However, there are cases when we don’t entirely rely on private keys because we have linked the key to the SHA (secure hash algorithm) fingerprint of the security certificate.

Security attestation

There’s always room for more security in Android. That’s why after building a protected Android app, it’s still important to acquire security attestation for the app. Security attestation provides proof that your app is secure.

There are two trustworthy sources that can attest to the security of your app.

- OWASP is a non-profit organization that conducts risk assessment and provides security tools and resources to help developers and organizations safeguard their apps against the most critical risks.

- SafetyNet is a set of APIs that enables Android developers to estimate the security level of the devices their apps run on.

Application security audit

An application security audit can also help ensure that an application is safe and secure. Demand creates supply, so plenty of software services are available to inspect the security in Android.

- ImmuniWeb MobileSuite

- Zed Attack Proxy

- QARKMicro Focus

- Android Debug Bridge

- CodifiedSecurity

- Drozer

- WhiteHat Security

- Synopsys

- Veracode

- Mobile Security Framework (MobSF)

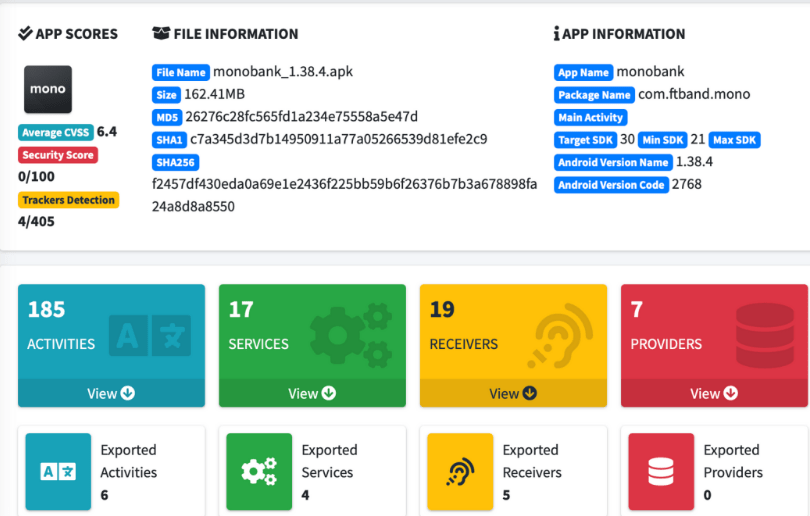

Let’s use the MobSF tool to check a banking app:

Here, one of the most critical indicators is the average CVSS, which stands for “common vulnerability scoring system.” CVSS is an open standard used for quantitative assessments of a computer system’s vulnerability, including the apps, and helps prioritize improvements. The lower the score, the better.

At the same time, MobSF might not show the CVSS score 100% accurate, because the tool only conducts static analyses. Sometimes, the tool considers factors non-secure, even though they are secure, because MobSF cannot recognize that developers have protected them.

Additional tools to improve Android app security

We recommend you work with these additional tools to strengthen your apps’ security.

- Keystore

- Keychain

- TEE Android

- StrongBox

- Biometric

Bonus tips and tricks

These are extra tools and frameworks to make the Android app almost unbreakable.

- Apktool unpack apk-files for software localization, app structure analysis, and so on.

- adb is installed as part of the Android-SDK, and allows you to manage Android OS devices. It uses a client-server approach with port 5037.

- dex2jar converts modified APK-files to a JAR (Java ARchive) files.

- JD-GUI, a utility used in combination with dex2jar, displays decompiled native code (JD stands for Java decompiler, part of the Java Decompiler project).

- Drozer is a framework with tools to identify mobile device and program vulnerabilities. The drozer framework takes on the role an application and interacts with the Dalvik virtual machine, other applications, and device operating systems.

- A VCG scanner is a tool for statistical analysis of native code. Programming languages it can analyze include C/C++, Java, C#, VB, and PL/SQL.

- Genymotion creates virtual machines to test Android apps.

- Pidcat is a program to read operation logs of Android programs and the Android operating system.